Mathematics of Trading: Edge

What It Means to Be Even Slightly Better Than Fair, and Why That Changes Everything

- What does it really mean to “have an edge” in markets?

- How is edge different from expected value?

- Why can tiny edges produce massive long-term PnL?

- Why do traders with real edges still lose money?

- How do noise, cost, and variance hide or erase edges?

- Why do edges decay over time, and how do we detect them?

In Post 1 we embraced uncertainty. In Post 2 we built the core tool for navigating uncertainty: expected value.

Now we ask the natural follow-up:

What makes one decision rule better than another? What makes a strategy “good”?

The answer is simple—yet extremely misunderstood:

A strategy is good if it has an edge. An edge exists if expected value is positive.

This post explains in depth what an edge is, why it’s powerful, why it’s fragile, and how to measure it.

What Is an Edge? (The crisp definition)

A trading edge is:

A repeatable condition that produces positive expected value over many independent trades.

Not prediction. Not confidence. Not “winning a lot.” Not intuition or chart patterns.

An edge is a mathematical advantage.

If a fair game has:

then having an edge means:

That’s the entire definition.

Edge Is Not Prediction

Beginners believe:

“Edge means I know what will happen next.”

Professionals believe:

“Edge means that across many uncertain outcomes, the distribution tilts slightly in my favor.”

Even the strongest edges lose frequently. Even perfect edges (e.g., biased coins) generate long losing streaks.

Edge is not about accuracy. Edge is about expectation.

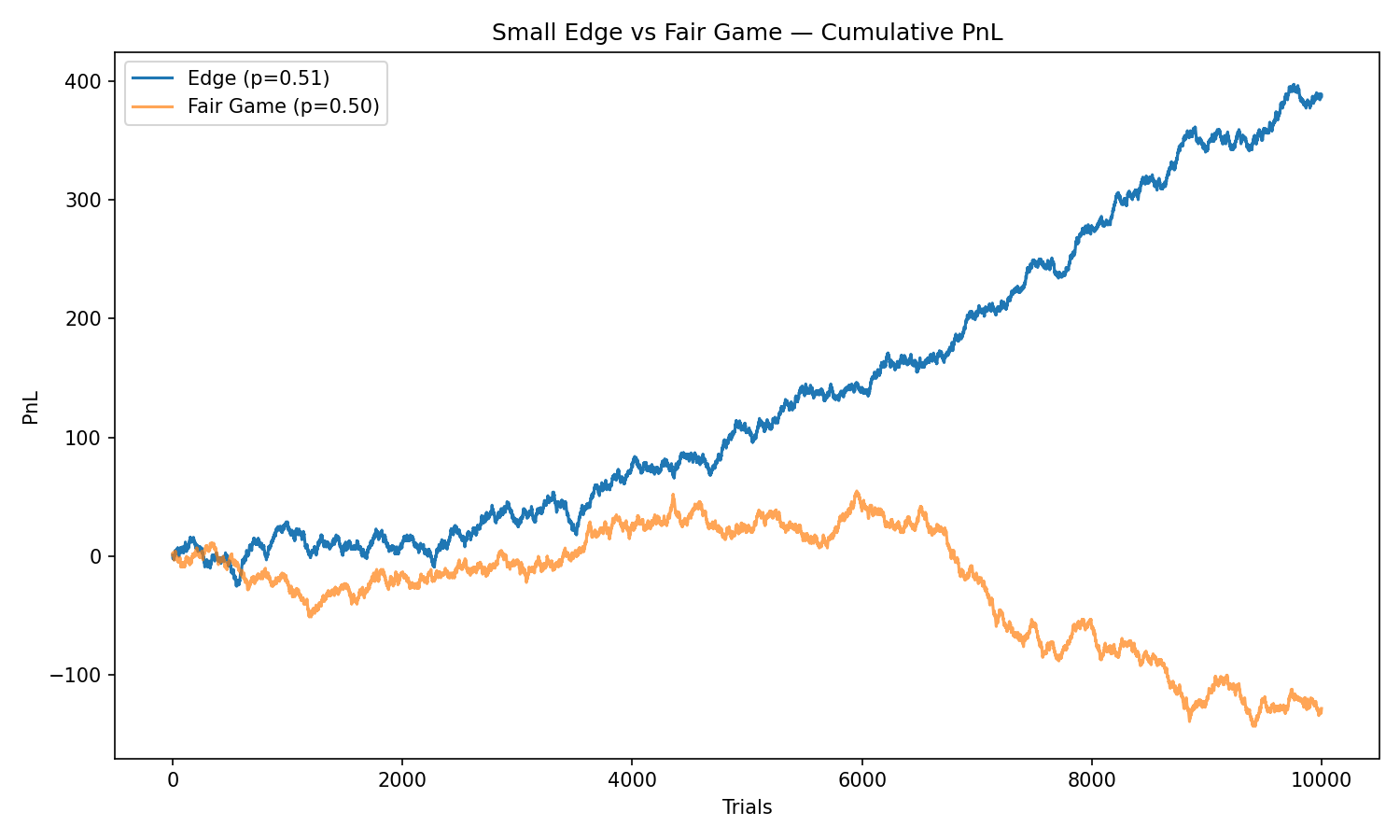

A Tiny Edge Is Still a Useful Edge

Consider a simple ±1 payoff game:

- Win probability = 0.51

- Lose probability = 0.49

- Payoffs = +1 or –1

Expected value:

Just two cents of edge per play.

This looks trivial, but when repeated many times, it creates a massive divergence from a fair game.

Even 1% advantage compounds dramatically across hundreds or thousands of independent trades.

This is one of the most important lessons in all of quantitative trading.

Gross Edge vs Net Edge — Costs Matter

Suppose you capture a tiny statistical advantage:

- Gross EV per trade = +0.02

- Transaction cost per trade = –0.02

Then:

Your real edge disappears.

This is why most naïve strategies fail:

- spreads

- commissions

- slippage

- adverse selection

- impact costs

Small edges die instantly when costs are ignored.

This is why professional traders spend enormous effort optimizing:

- execution

- order placement

- routing

- timing

- position sizing

Execution itself can be an edge.

Why Traders With a Real Edge Still Lose Money

You can have positive expected value and STILL:

- blow up

- hit deep drawdowns

- have awful periods

- lose money for months

- give up before the edge expresses itself

Why?

Because edge describes the average, not the path.

Variance describes the path. And variance is often much larger than people expect.

Thought experiment

A strategy with EV = +0.2 per trade and variance = 10 per trade can easily go:

- –50

- –80

- –100

before drifting upward.

This is why trading requires survival. You must live long enough for the edge to matter.

Where Edges Come From

Edges tend to fall into a few major families.

A. Behavioral Edges

Markets are driven by humans (and algos trained on humans).

Common behaviors:

- fear

- greed

- crowding

- panic selling

- FOMO buying

These produce statistical tendencies:

- momentum (herding)

- mean reversion (overshooting)

- volatility clustering

Behavioral edges often decay as participants adapt, but while they exist, they can be strong.

B. Structural Edges

These come from the architecture of markets.

Examples:

- market making / spread capture

- volatility risk premium

- option decay / theta

- overnight return effects

- index rebalancing flows

These edges exist because markets must function — someone must exchange liquidity or bear certain risks.

C. Informational Edges

Where one participant processes reality more effectively:

- statistical arbitrage

- alternative data

- order book microstructure

- machine learning prediction of short-term flows

These are often short-lived and arms-race-driven.

D. Execution Edges

Small execution improvements add up:

- less slippage

- better fill rates

- smart order timing

- hidden liquidity detection

Even 1 cent per trade is huge scaled across millions of units.

E. Risk Management Edges

Two traders with the same signal can have completely different results based on:

- sizing

- volatility scaling

- stop logic

- leverage discipline

Survival is itself an edge.

Measuring an Edge — The Hard Part

It is easy to believe you have an edge. It is much harder to measure one.

A real edge must be:

- positive EV

- statistically significant

- repeatable

- robust across changes

- resistant to decay

- economically sensible

- net positive after costs

Most “edges” vanish under even minimal statistical scrutiny.

The Edge Lifecycle: Discovery → Exploitation → Crowding → Decay

Every edge goes through the same evolutionary path:

- Discovery — someone finds it

- Exploitation — they make money

- Crowding — others copy it

- Decay — competition removes the inefficiency

Even strong edges tend to decay over time.

This is why quant strategies must continually evolve.

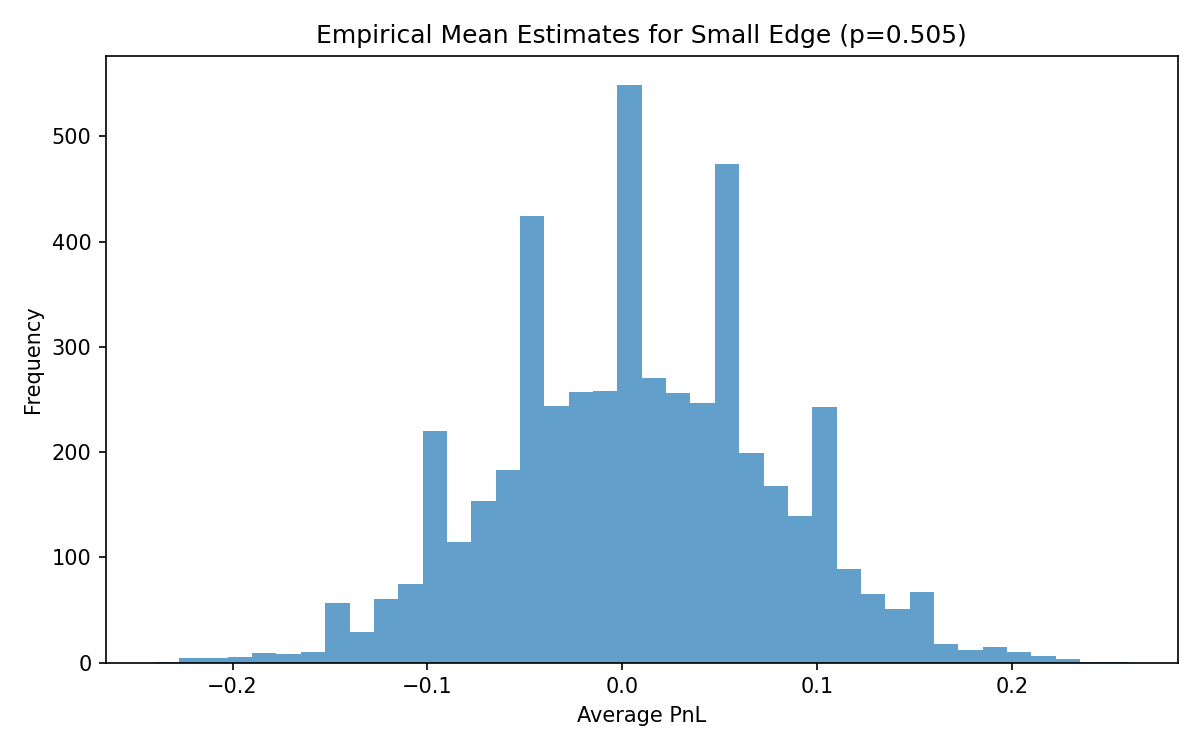

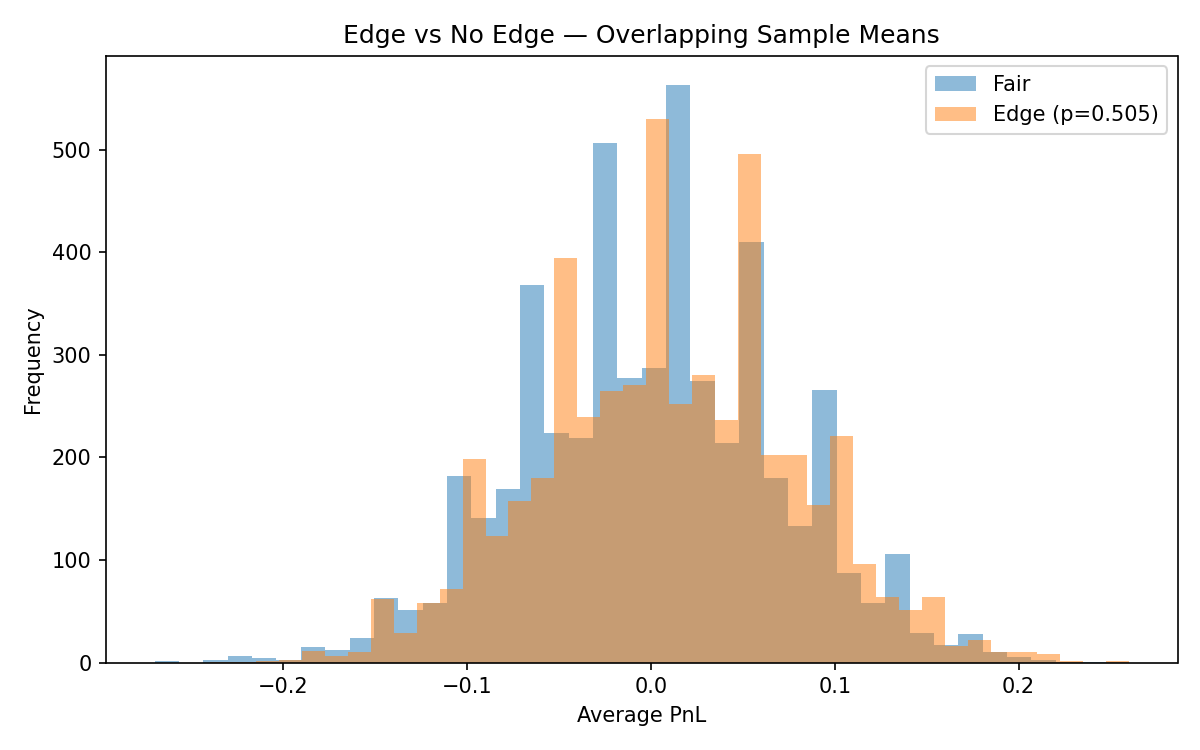

Small Edges Are Very Hard to Detect

Suppose a strategy has:

- p = 0.505

- Payoff = ±1

True EV:

Let’s simulate 200-trade samples.

Most sample means will be nowhere near 0.01. Many will be negative.

Now compare to a fair coin (p = 0.5). Their distributions overlap heavily.

This is the core difficulty of edge detection. Small true edges hide inside large noise.

This is why large sample sizes and Monte Carlo are essential.

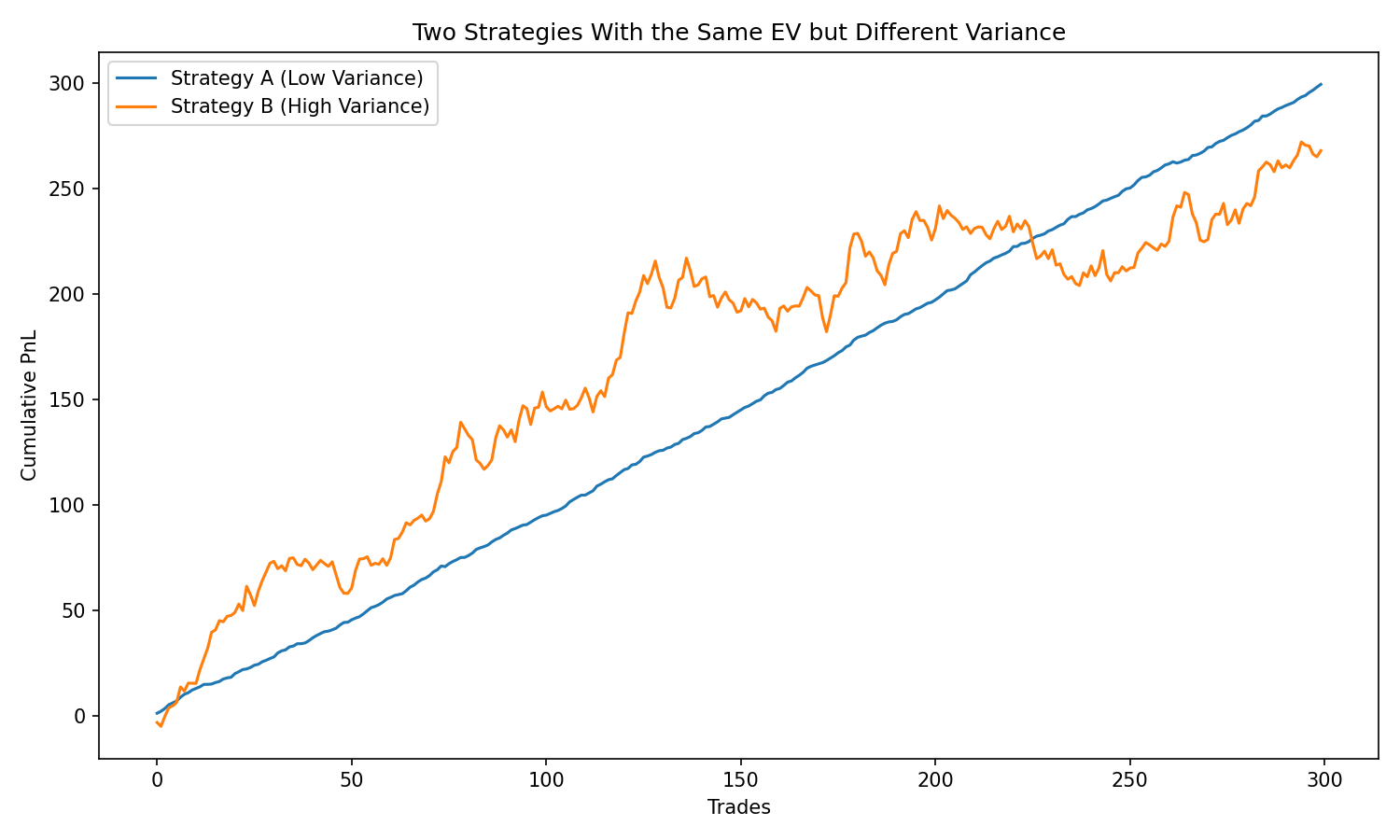

Two Strategies Can Have the Same EV but Feel Completely Different

Consider:

Strategy A

Frequent small wins, occasional small losses Low variance EV = +1

Strategy B

Frequent small losses, occasional very large wins High variance EV = +1

Same expected value. Completely different emotional experience.

This matters because most traders quit not from negative EV, but from psychological discomfort caused by variance.

Having an Edge Is Not Enough — You Must Survive

To succeed in trading, you need two things:

1. A real edge (EV > 0)

2. The ability to survive long enough for the edge to manifest

Survival requires:

- position sizing

- capital allocation

- volatility control

- avoiding leverage-induced ruin

Many traders have an edge but blow up before they ever realize it.

This leads directly to:

- Post 4 — Probability Distributions

- Post 5 — Variance, Volatility & Drawdowns

- Post 6 — Risk of Ruin

Together, these explain why edges fail in practice.

12. Key Takeaways

- An edge is a repeatable positive-EV condition

- Edge is not prediction — it survives uncertainty

- Tiny edges compound massively

- Costs can destroy small edges

- High variance can hide or overwhelm real edges

- Edge decay is inevitable

- Small edges require huge samples to validate

- Same EV can produce wildly different PnL paths

- Survival is required to realize any edge