Mathematics of Trading: Modeling Randomness

Random Walks → Brownian Motion → Geometric Brownian Motion → Monte Carlo Simulation

How Markets Generate Noise, How We Model It, and Why Every Trading Strategy Exists Inside a Cloud of Possible Futures

Financial markets look noisy and chaotic:

- prices wiggle unpredictably

- shocks appear out of nowhere

- paths diverge dramatically

- volatility comes in clusters

- trends emerge and collapse

To understand:

- edge

- variance

- drawdowns

- ruin

- tail events

- strategy testing

- stress scenarios

we must understand randomness.

This post shows:

- How randomness is modeled mathematically

- How prices evolve in uncertain environments

- Why Brownian motion is the backbone of modern finance

- Why GBM is the standard model for price dynamics

- Why Monte Carlo simulation is essential for real-world risk analysis

This is the most mathematically important post so far.

Randomness: The Foundation of Market Behavior

Markets look random even when they aren’t purely random.

They are driven by complex forces:

- order flow

- liquidity pressure

- news shocks

- behavioral cascades

- algorithmic interactions

Even so, randomness provides a tractable mathematical framework that captures essential features of market movement.

We begin with the simplest model.

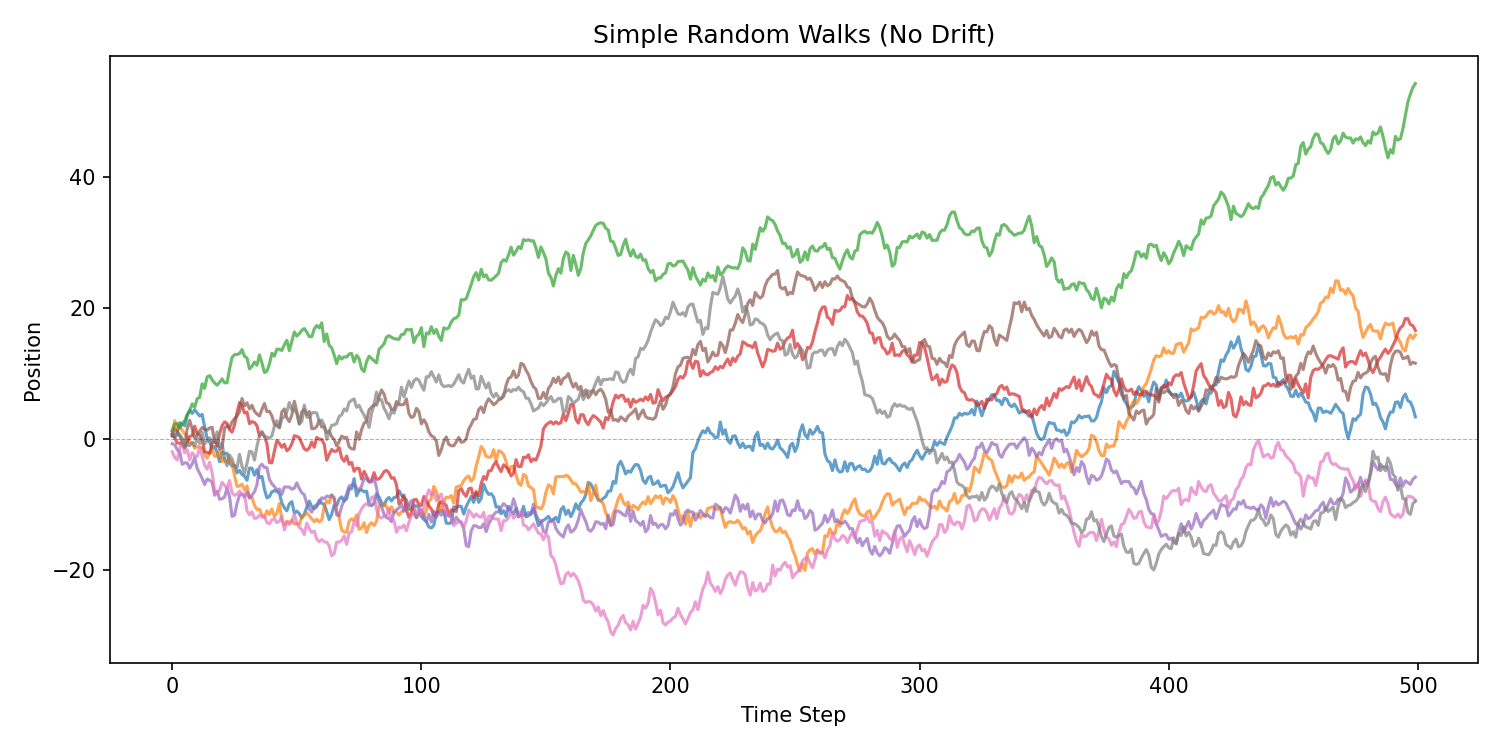

Random Walks: The First Market Model

A random walk evolves by adding random increments:

Where:

A random walk captures:

- short-term unpredictability

- long-term variance growth

- path dependence

- divergence between sample paths

Variance grows linearly

Meaning:

- uncertainty increases with time

- small randomness accumulates into large randomness

Distribution approaches normal

even if the step distribution is simple.

Random walks already look surprisingly like real markets.

But prices cannot go negative — that requires refinement.

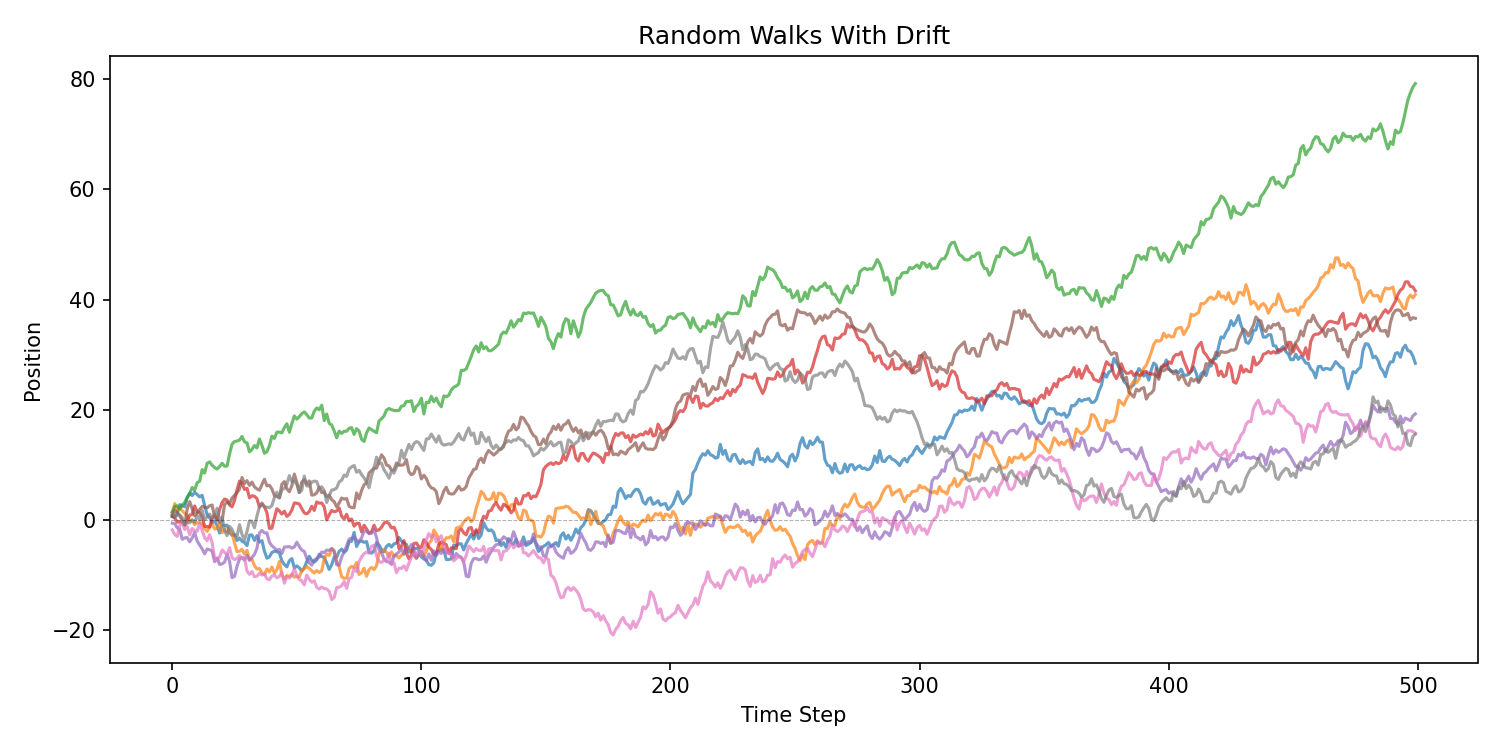

Random Walks With Drift

Markets exhibit long-term upward drift (risk premium).

We add a deterministic trend:

Now the process trends upward on average, but remains unpredictable path-by-path.

Still, this model is additive — markets are multiplicative.

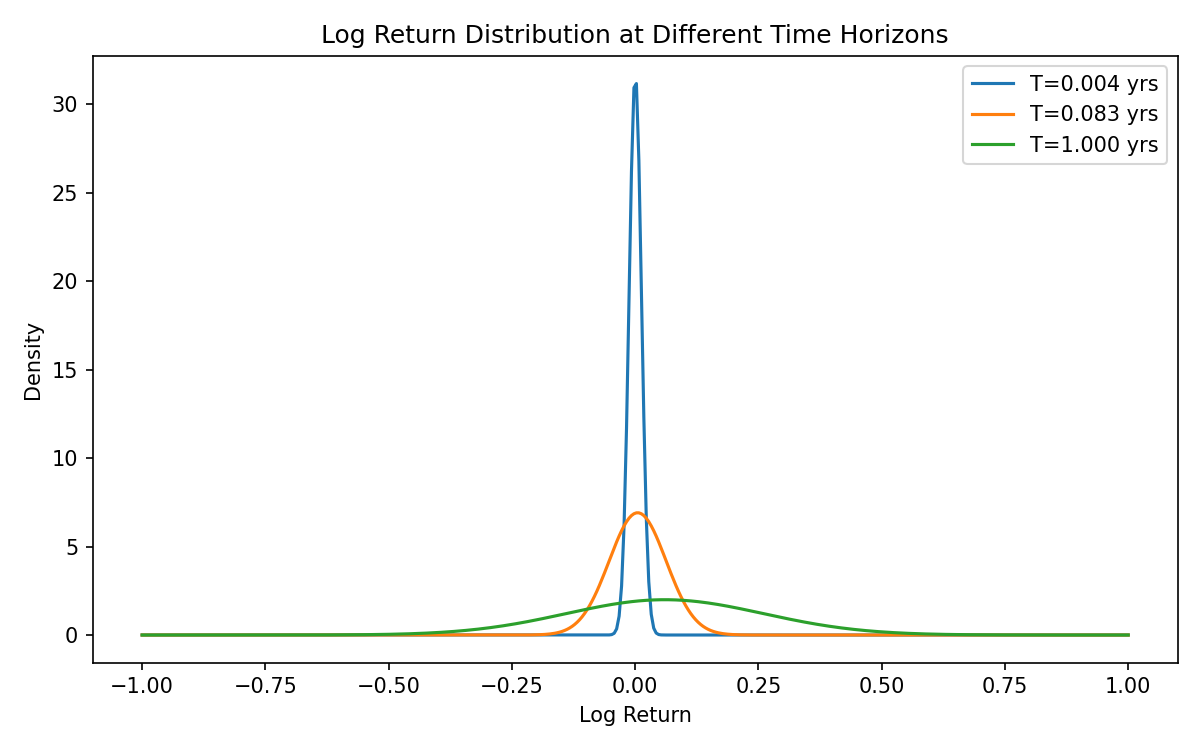

Log Returns: Fixing the “Negative Price” Problem

Markets move in percentages, not points.

- A 1% move at 100 = +1

- A 1% move at 200 = +2

So price changes scale with price.

We model log returns:

Log returns are:

- additive

- stable

- symmetric-ish

- always yield positive prices

If log prices follow a random walk:

then prices are always positive.

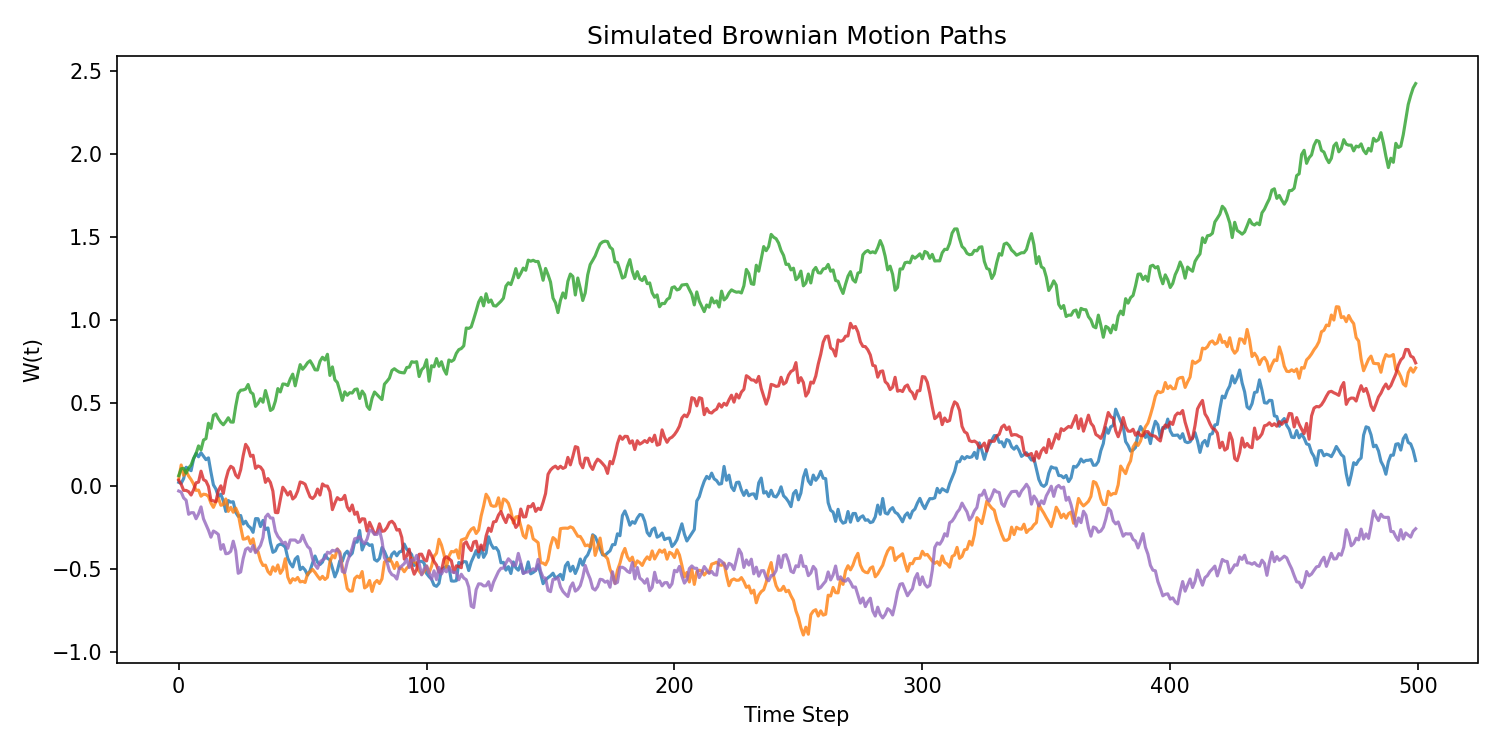

Brownian Motion: Continuous-Time Randomness

Discrete random walks converge to a continuous-time stochastic process:

Brownian motion (also called Wiener process).

Properties

- ( W(0) = 0 )

- Independent increments

- Normal increments

- Variance grows linearly:

- Continuous but nowhere differentiable (capturing jagged market behavior)

Brownian motion is the mathematical engine of nearly all classical financial modeling.

Brownian Motion With Drift

Add deterministic growth:

Interpretation:

- : predictable drift

- : stochastic noise

This structure maps directly to short-term unpredictability + long-term trend.

Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM): The Standard Model for Asset Prices

Raw Brownian motion can go negative — unacceptable for prices.

GBM fixes this:

This implies:

Consequences

- prices stay positive

- log returns are normal

- volatility scales as

- paths diverge exponentially

- uncertainty grows multiplicatively

GBM is used in:

- Black–Scholes

- VaR models

- forecasting tools

- Monte Carlo simulators

- quantitative trading research

It is not perfect — but it is the essential baseline.

GBM vs Real Markets: Where the Model Breaks

GBM assumes:

- constant volatility

- no jumps

- normal returns

- no clustering

- no skewness

- no fat tails

Real markets have:

- volatility clustering

- fat tails

- negative skew

- jumps

- regime shifts

- autocorrelation in volatility

GBM is the starting point. Monte Carlo is how we test deviations from it.

Monte Carlo Simulation: Modeling Thousands of Futures

A single historical backtest gives one path.

Monte Carlo simulation gives thousands.

It answers:

- How wide is the distribution of possible outcomes?

- How deep can drawdowns get?

- How frequently does ruin occur?

- How much tail risk exists?

- How volatile is performance across paths?

Monte Carlo = risk in full resolution.

Monte Carlo Example Set 1 — Gambling Games

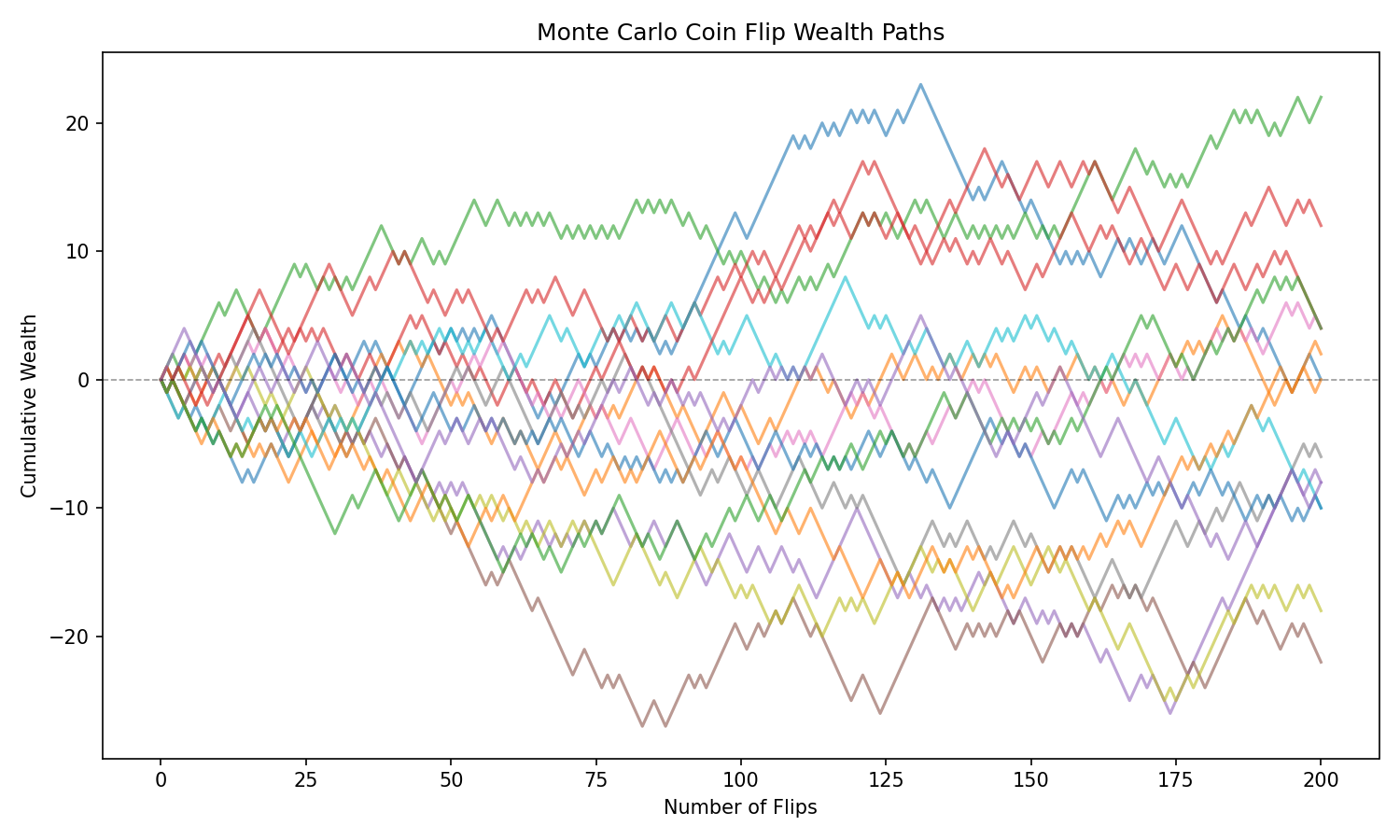

Example A: Coin Flip Wealth Paths

Game:

- +1 for heads

- –1 for tails

- 200 flips

Simulate 10 paths.

Observations:

- same rules, wildly different outcomes

- variance compounds

- prediction is impossible

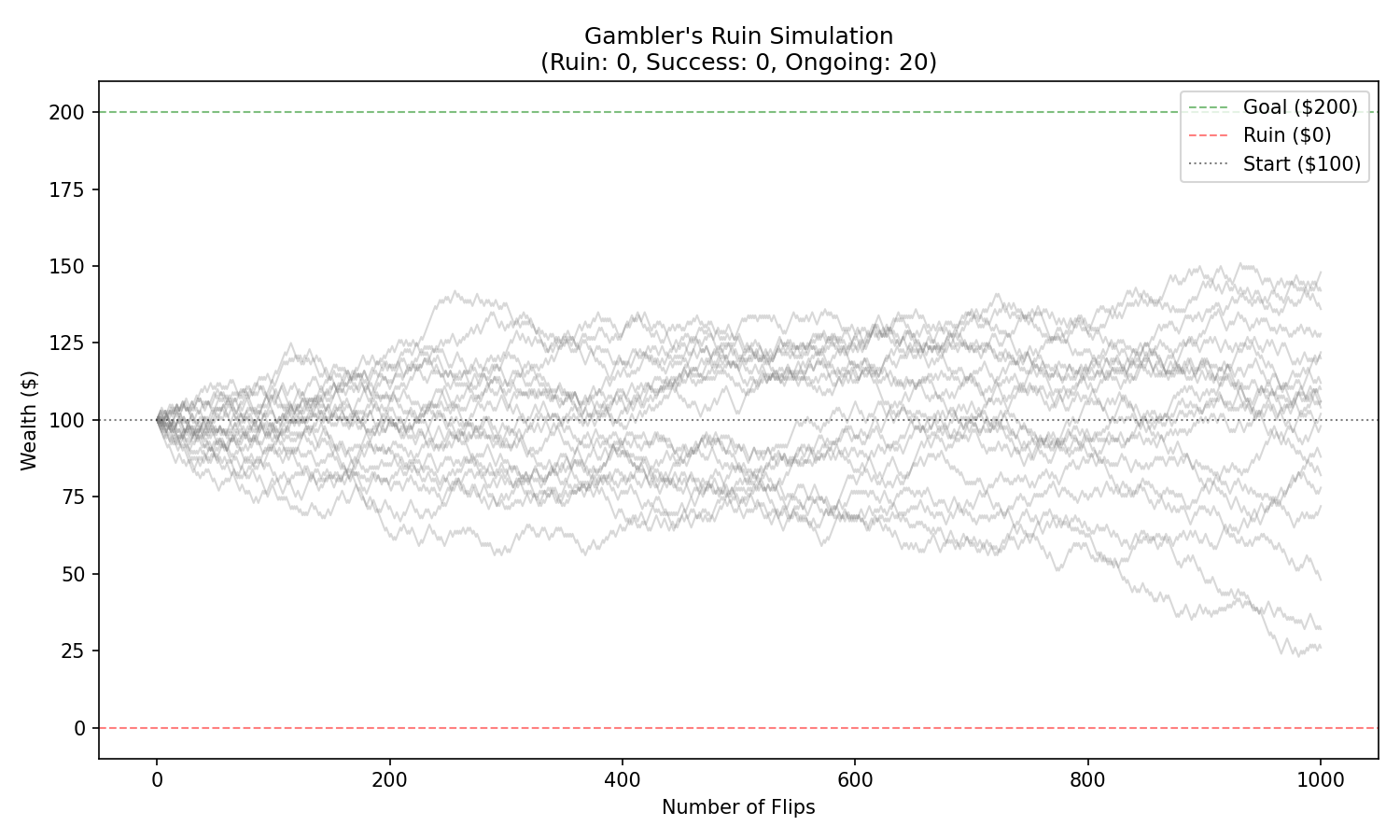

Example B: Gambler’s Ruin

Start with 1 per flip Goal: reach 0

Monte Carlo estimates:

- probability of ruin

- distribution of time to ruin

- expected play length

- impact of unfavorable odds

This problem is the ancestor of modern risk-of-ruin theory.

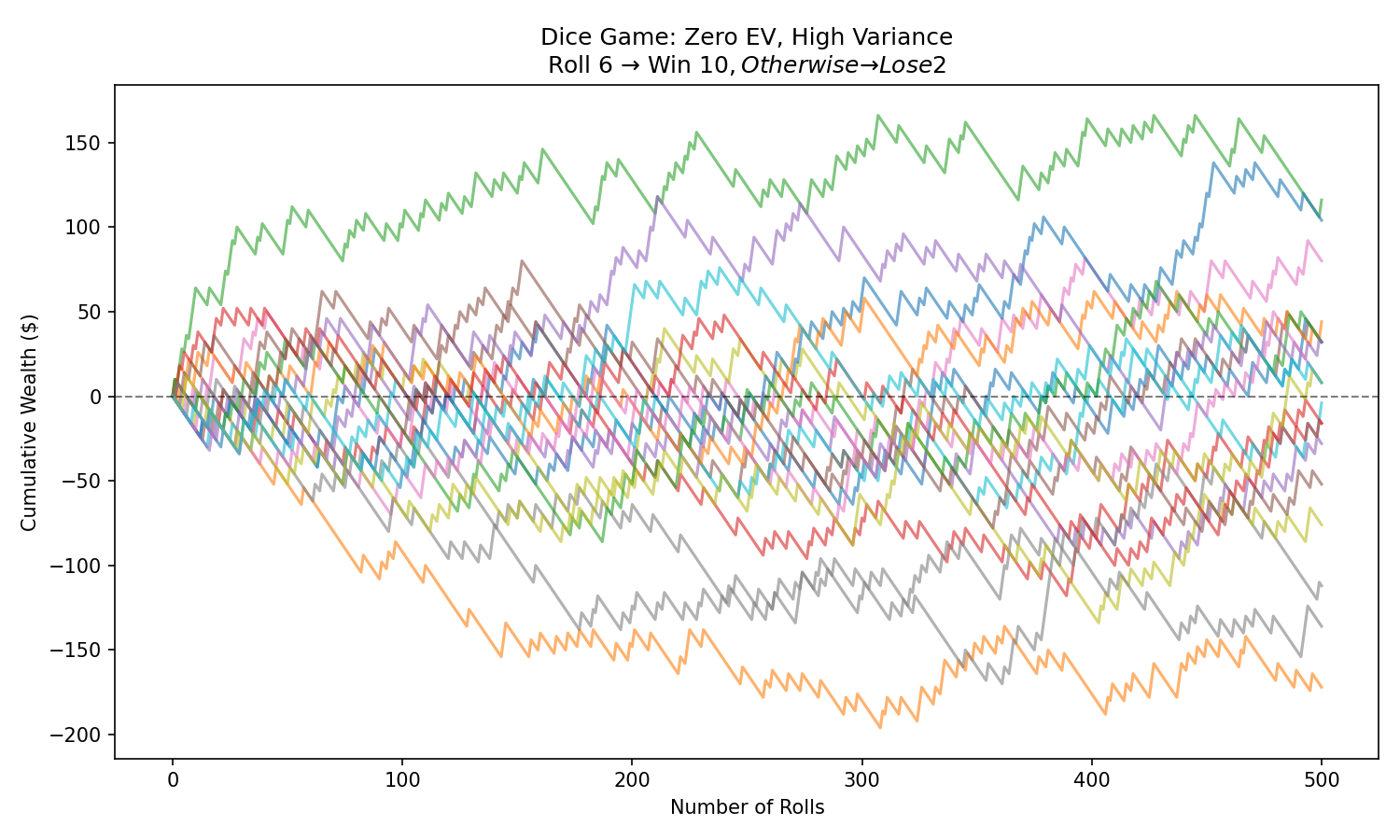

Example C: Dice Game EV Simulation

Game:

- roll a die

- 6 → win $10

- otherwise → lose $2

Analytical EV = 0

But Monte Carlo shows:

- long drawdowns

- variance around 0

- risk of ruin despite fair odds

11. Monte Carlo Example Set 2 — Markets

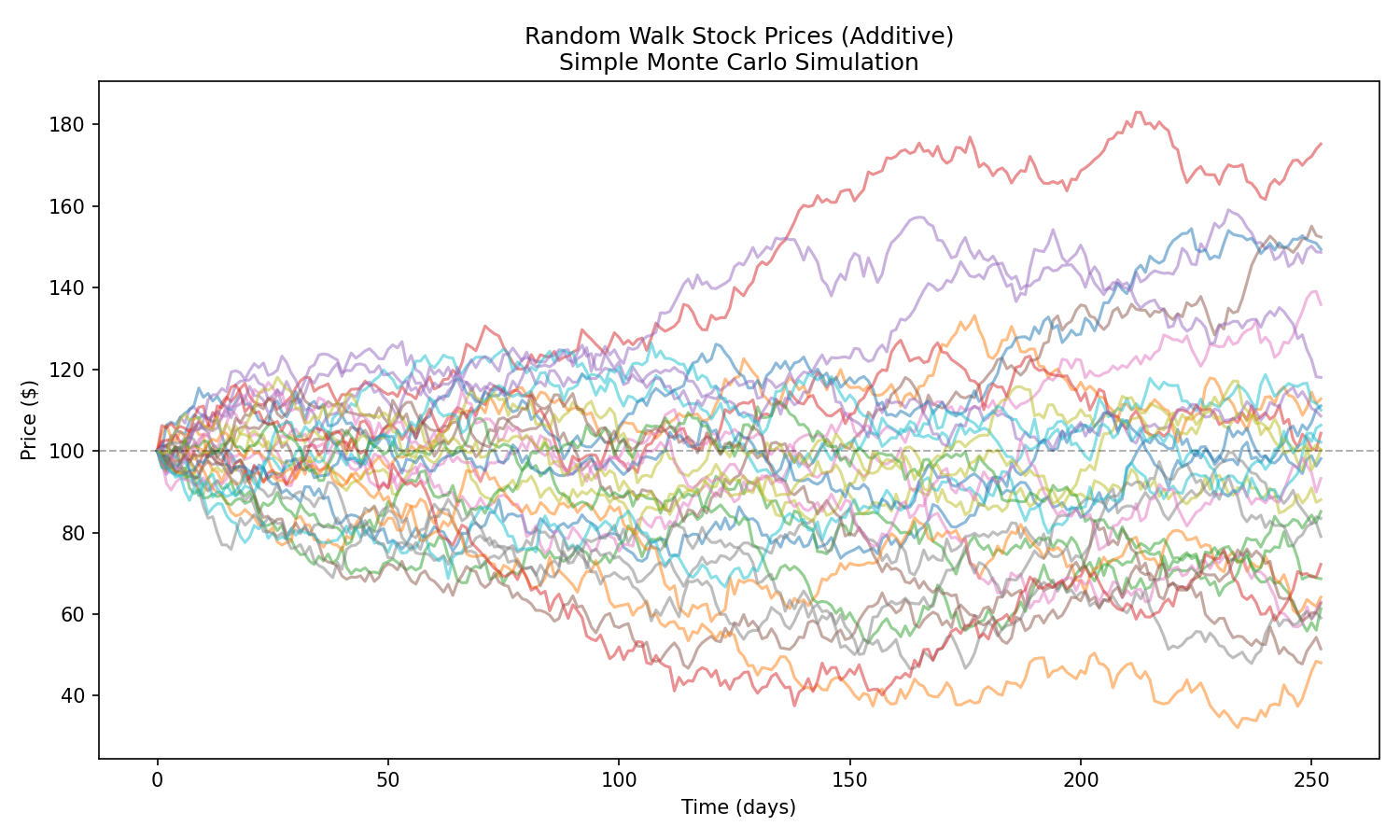

A. Random Walk Stock Prices

The simplest price simulation.

Reveals:

- range of possible trajectories

- divergence of sample paths

- exploding uncertainty over time

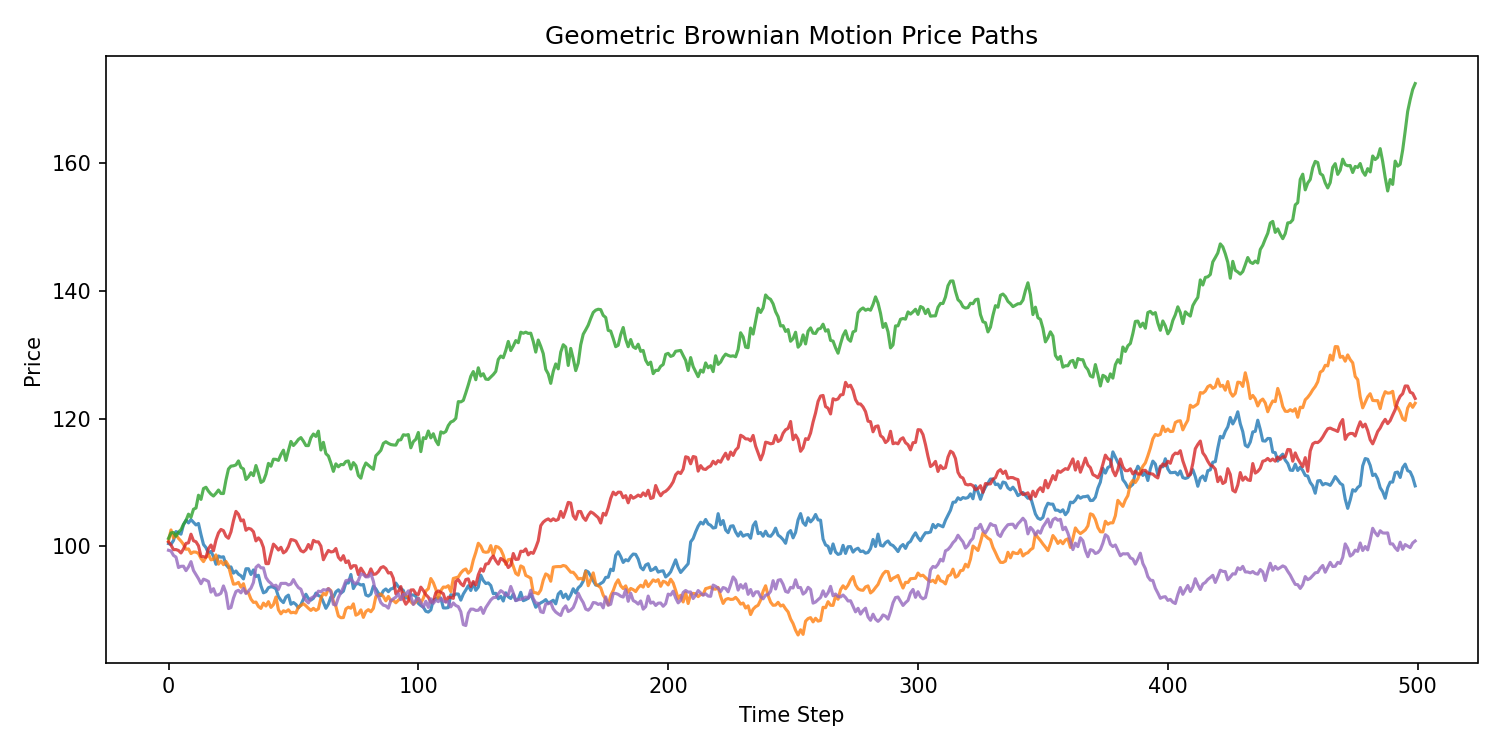

B. GBM Price Simulations

For GBM:

with .

Simulate 50 paths:

- drift nudges upward

- volatility broadens the cone

- uncertainty grows exponentially

- extreme paths appear naturally

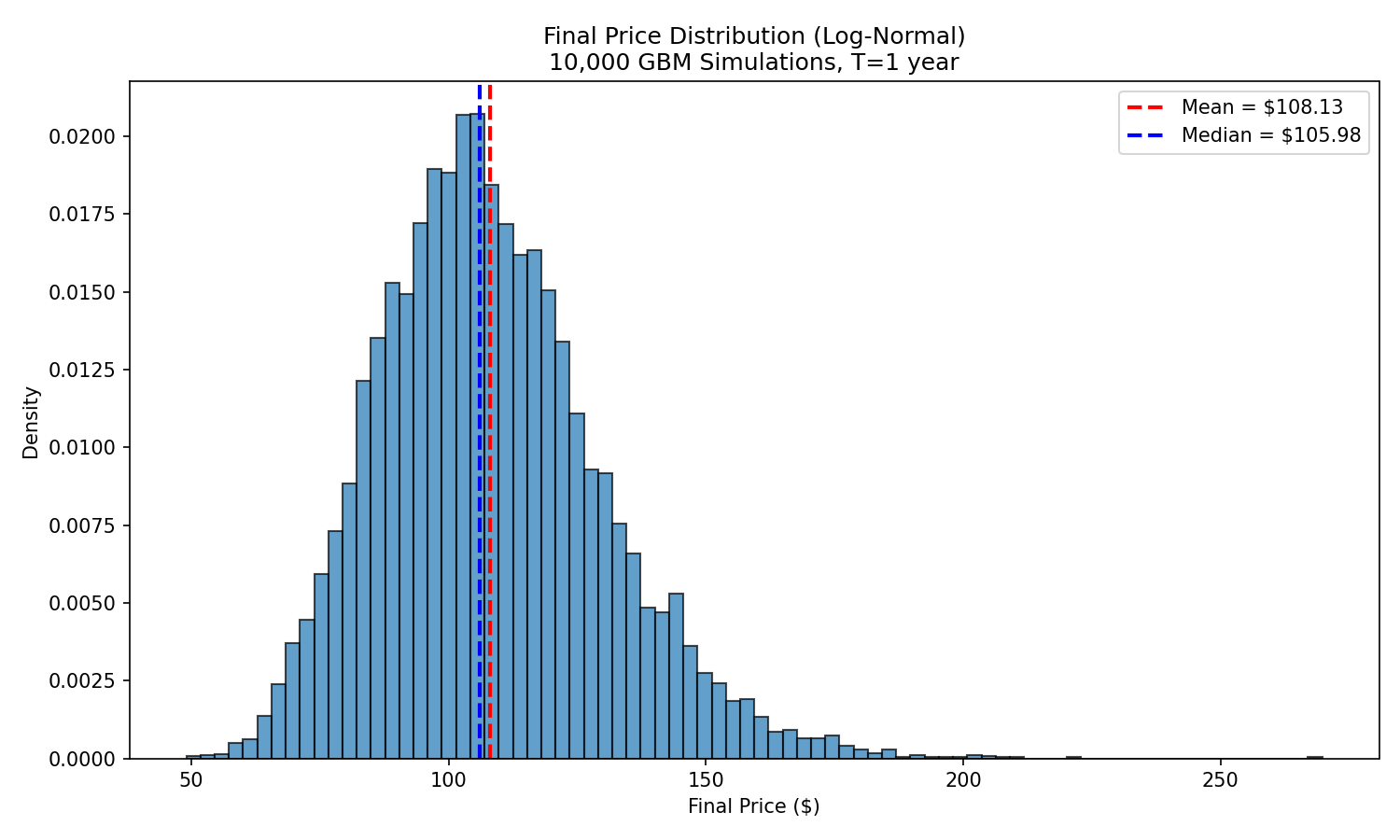

C. Final Price Distributions

Simulate 10,000 paths.

Ending prices follow a log-normal distribution:

- median < mean (volatility drag)

- fat right tail

- left skew from price floor at 0

This distribution underlies:

- Black–Scholes

- geometric mean return

- exponential wealth dynamics

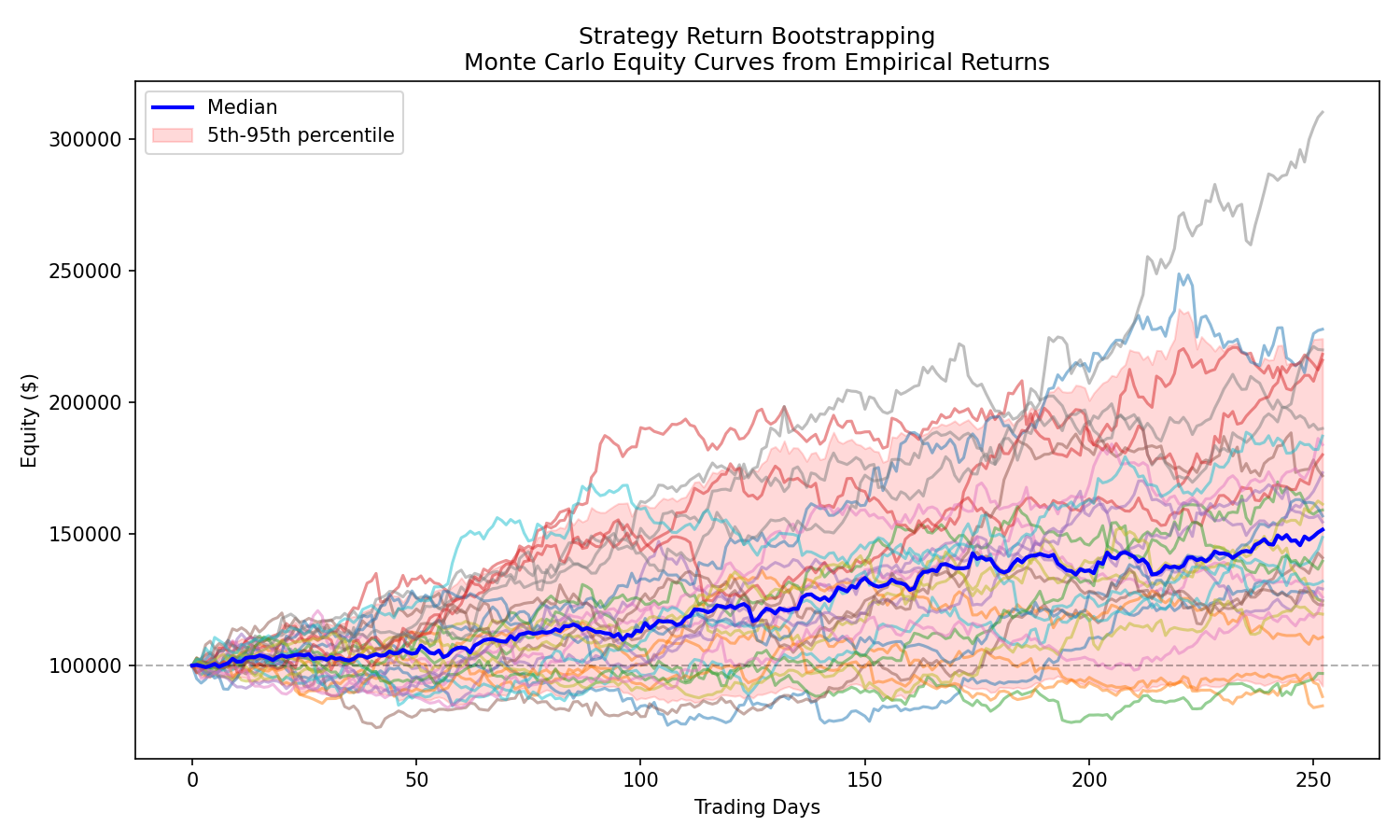

D. Strategy Return Bootstrapping

Let strategy returns follow some empirical distribution.

Simulate equity curves:

Repeating thousands of times reveals:

- expected drawdown

- 95% worst-case drawdown

- variability of Sharpe ratio

- likelihood of different future paths

No single backtest can reveal this.

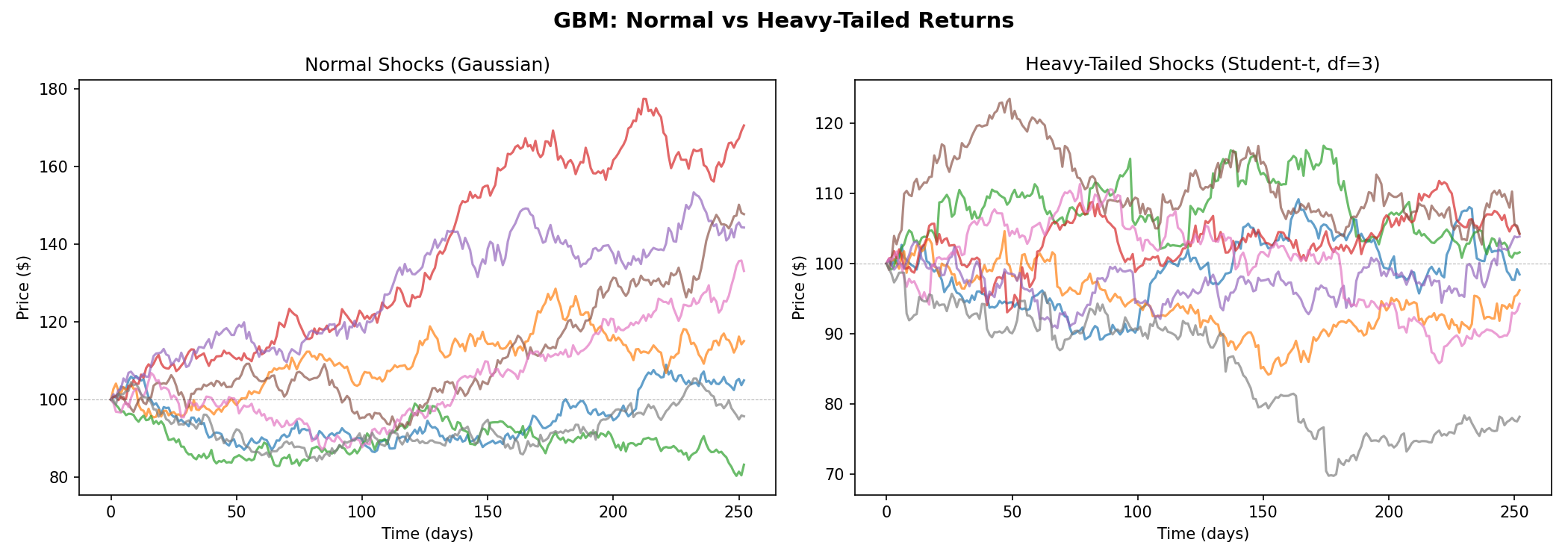

E. Heavy-Tailed Crash Scenarios

Replace normal shocks with Student-t shocks:

This introduces:

- more crashes

- fatter tails

- more ruin events

- more realistic crisis dynamics

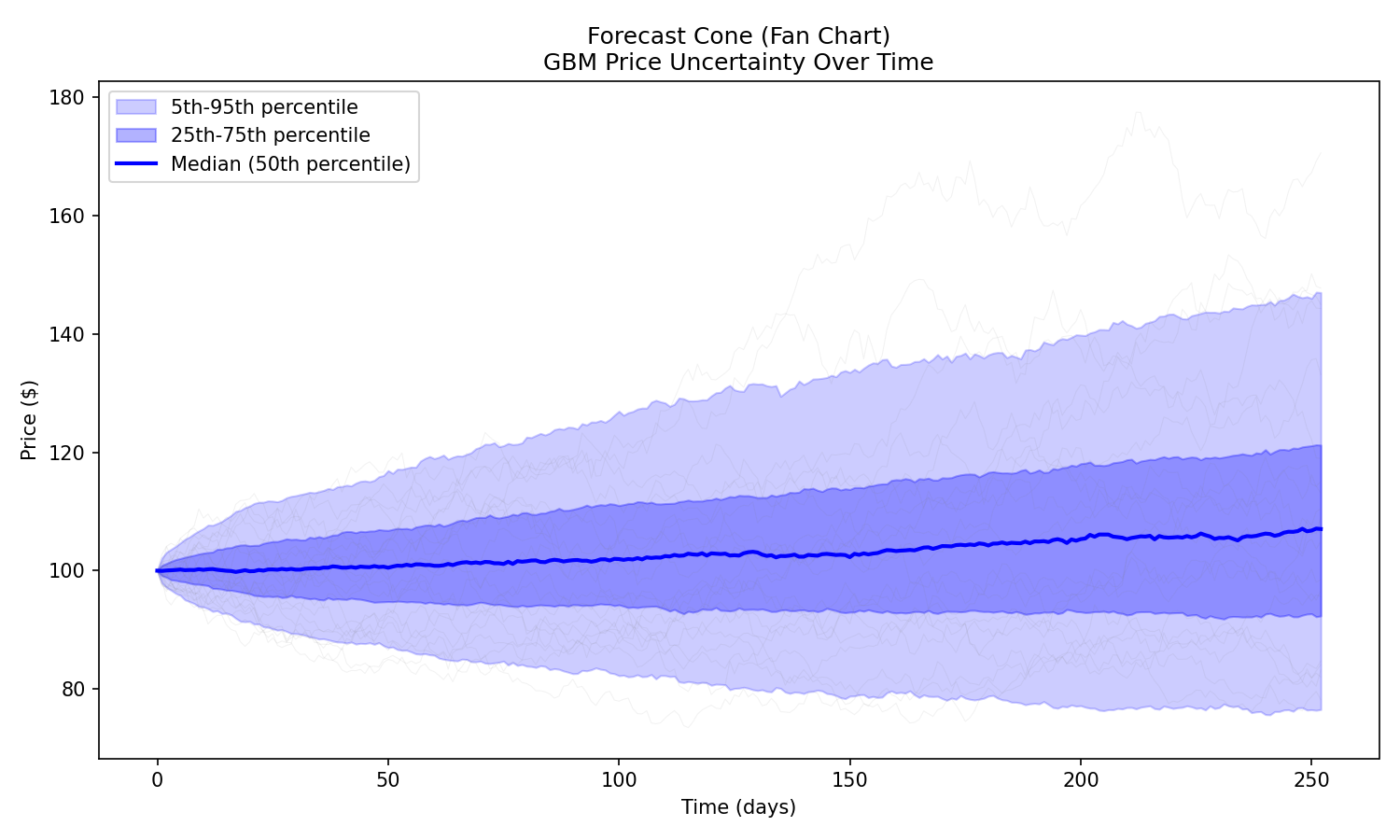

F. Forecast Cones (Fan Charts)

Compute percentiles across paths:

- 5th percentile (worst case)

- median

- 95th percentile (optimistic)

This creates the "uncertainty cone" used in:

- portfolio management

- risk reporting

- long-term forecasting

Why Monte Carlo Is Essential

Backtesting answers:

Does this system work on one historical path?

Monte Carlo answers:

Does this system survive thousands of plausible futures?

Monte Carlo exposes:

- hidden fragility

- left-tail danger

- sizing issues

- variance shock sensitivity

- survival probability

- robustness to noise

- drawdown uncertainty

Professional traders never deploy strategies without Monte Carlo analysis.

Key Takeaways

-

Random walks are the base model of unpredictability

-

Brownian motion is the continuous-time limit

-

GBM ensures positivity & multiplicative returns

-

Markets deviate from GBM but GBM is the essential baseline

-

Monte Carlo simulation is the only way to understand:

- drawdowns

- ruin

- performance variability

- tail risk

- robustness

Every trading strategy is not one equity curve. It is a distribution of equity curves.

Monte Carlo lets you see that distribution.